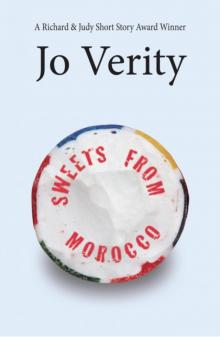

Sweets From Morocco Read online

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Part I – 1954

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part II – 1962

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part III – 1968

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Part IV – 1976

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Part V – 1978

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part VI – 1980

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Part VII – 1987

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Part VIII – 1988

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Part IX – 1991

Chapter 38

Part X – 1996

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Part XI – 1998

Chapter 43

Part XII – 2005

Chapter 44

Acknowledgements

About Honno

About Jo Verity

Other titles by Jo Verity

Copyright

Sweets from Morocco

by

Jo Verity

HONNO MODERN FICTION

For Nick Evans

I

1954

Chapter 1

The rectangular garden was divided, half-and-half, into lawn and vegetable patch and in the far corner, between the row of runner beans and the tall privet hedge, two children sat on their heels. The girl’s dark-brown hair hung forward in heavy plaits, framing her solemn face, and she was frowning as, with a short length of bamboo cane, she agitated murky liquid in the jam jar which stood between them on the red soil. The boy looked on, glancing between the jar and the girl’s face, seeming to seek assurance that events were on course. His hair was brown, too, but less vibrantly so, his skin, paler, his movements more hesitant, as if he were her sun-bleached replica.

She stood up, holding the jar aloft and inspecting its swirling contents, then, with her free hand, flicked the plaits back over her shoulders. ‘I’ll go first.’

The boy scrambled to his feet and, now that they were both standing, it was possible to see that he was a shade taller than his sister. ‘Must we?’

She dismissed his question by raising the rim of the jar to her lips, pausing long enough to ensure his face contorted with revulsion before taking a hearty gulp. She swallowed and, mouth fixed in a triumphant smile, offered the concoction to him. ‘Now you.’

The boy shoved both fists into the pockets of his khaki shorts and turned his head to one side, avoiding her glare.

‘Lewis. Drink it.’

‘But…’

‘Drink it. Or I’ll never speak to you again.’ She thrust the jar close to his mouth.

He stood his ground but dipped his head, closing his eyes and screwing up his face as if he had already downed a dose of the disgusting brew.

‘You promised, Lewis. Come on. It’s only gravy browning and water.’

‘And vinegar. And bi carb.’

She tried another tack. ‘We could do blood-mingling instead, if you like,’ but he didn’t respond and she stamped her foot. ‘Don’t be such a ninny.’

A reedy voice put an end to the stalemate. ‘Tessa? Lewis? Come and wash your hands before dinner.’

Lewis edged to the end of the bean row. ‘Coming, Gran,’ he shouted in the direction of the voice, disclosing their hiding place and gaining a let-up from his sister’s demands.

‘You know what breaking your promise means, don’t you? You’ll be cursed forever.’ Tessa caught the back of her brother’s tee shirt. As he twisted, trying to break from her grasp, she doused his feet with the contents of the jar. Some of the liquid splashed on to the ground, escaping in dusty rivulets across the compacted soil, but there was still plenty to saturate his new sandals – the second pair he’d had that summer as his feet had grown a size-and-a-half since Whitsun. He let out a squeak, like brake blocks binding on the rim of a bicycle wheel, flexing his feet, listening to the kissy slurp of liquid surging up through the patterns punched in the leather.

Tessa dropped the jar and hugged him. ‘Don’t cry, Lew. Please don’t cry. Here, take them off.’ She knelt and, whilst Lewis placed a hand on her shoulder to steady himself, she pulled the sandals off, not bothering to undo the buckles, still stiff with newness.

‘It’ll leave a mark. What’ll I tell Mum?’ he fretted.

‘Mum’s not here, stupid.’

‘Dad then.’

She slapped one shoe against the other then placed them on the ground. Reaching beneath her gingham skirt, she dragged her knickers down to her knees then slipped them off. She scrubbed away with this improvised duster, removing as much liquid as she could before placing the sandals on the path, in full sun but out of sight of the house. ‘There. They’ll be dry by the time we’ve had dinner. Gran won’t notice you’ve got bare feet.’ She wriggled back into her knickers.

‘Lew-iiis. Tess-aaa.’ The calling voice rose on the second syllable of the names. ‘I won’t tell you again.’

‘C’mon, slow coach.’ Tessa grabbed her brother’s hand and they ran across the lawn to the back door.

Their grandmother was in the kitchen, stationed at the gas cooker, prodding the contents of two simmering pans with a vegetable knife. She nodded towards the sink. ‘Wash your hands here, where I can keep an eye on you. I don’t want you disappearing again.’

Tessa ran cold water into the chipped enamel bowl and they dunked their grubby hands, drying them on the towel which hung from the handle of the larder door. Then the children took their places, side by side, at the table whilst their grandmother strained the vegetables through a colander, held at arms length to keep the rising steam away from her spectacles. For the past three weeks, the sun had blazed out of a near-cloudless sky and, as the heat built, there was talk of record-breaking temperatures. Despite this, Gran wore a cardigan over a summer dress, the whole lot swaddled in a washed out pinafore. Her hair was an improbable shade of orange, perfectly straight to within an inch or two of the cut ends where it erupted in a crinkly border. Tessa and Lewis often discussed their grandmother’s hair, never daring to ask how she achieved this effect but, given its likeness to knitting wool which had been unravelled from an unwanted garment, they guessed it had been reached in a similar way.

‘What’s for pudding, Gran?’ Tessa asked before she’d taken more than a couple of mouthfuls of food.

‘Pudding? There’ll be no pudding until I’ve seen two clean dinner plates.’

‘Only two?’ Tessa asked. ‘What about yours?’

The woman shook her head. ‘You’re too sharp, young lady. You’ll cut yourself one of these days.’ After a short silence she continued, ‘I don’t know why they give you these long school holidays. And I certainly don’t know what’s got into you two.’ Lots of their grandmother’s sentences began ‘I don’t know why…’ or ‘I don’t know what…’ as if life were a series of conundrums to which she would never find a satisfactory answer.

/>

Tessa knew the answers to both. Miss Drake had explained to the class that the long summer holidays had come about hundreds of years ago, to enable children to help their families at harvest time. The school that she and Lewis attended was in a suburb, where the largest garden was, at most, twice the size of theirs, making nonsense of this explanation. But, like admitting that she no longer believed in Father Christmas, it would be crazy to point it out and risk the holiday being shortened. And as for what had ‘got into’ her, Gran must be stupid if she couldn’t work that one out. The birth of her new brother was what had ‘got into’ her.

Lewis hooked his heels over the strut of the chair and spread his toes as wide as they would go. Simply having nothing on his feet made him feel heroic. His mother told him off if he went about barefoot, warning that he would stand on a piece of glass or get splinters from the woodblock floor or catch those awful things from the swimming baths – verrucas, that was it. He’d get verrucas and the doctor would have to dig them out. This didn’t make sense, though, because how could anyone go swimming unless their feet were bare?

He dissected the luncheon meat on his plate, enjoying the ease with which the blunt-ended knife cut through the soft pinkness of each slice. Two, four, eight. Two, four, eight. Sixteen neat rectangles.

‘Don’t play with your food, Lewis, there’s a good boy.’

How was he supposed to cut it up? Diagonal cuts generated a series of frivolous triangles and if he rolled a slice up and jammed it in, she would surely shout at him for overfilling his mouth. There were grownups – Uncle Frank, for example – whom Lewis knew would be happy to discuss this dilemma, but not Gran. So in order to secure the bowls of strawberry jelly and evaporated milk that he’d spotted on the slab in the larder, he let it go unchallenged.

‘Gran?’ Tessa stirred the contents of her bowl, reducing it to an orangey-pink liquid, marbled with bright red. ‘When’s Mum coming home?’

Doris Lloyd’s face took on the soppy expression of someone seeing an orphaned puppy. ‘Are you missing her? Not long now. But she needs to get her strength back. She’ll have her hands full with you two and your new baby brother.’

Tessa continued stirring, clattering her spoon in the glass bowl whilst Lewis looked on uneasily. ‘We don’t want a brother. Or a sister. We never asked her to get one, did we, Lewis?’ She nudged him.

He shrugged.

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Tessa,’ their grandmother said. ‘It’ll be wonderful, having a baby in the house again.’

‘Why? Babies don’t do anything. They just cry and wet themselves.’

Doris Lloyd stood up and gathered the empty bowls. ‘That’s enough of that. Off outside, you two. I’ve got things to do.’

The children returned to the garden. Lewis’s sandals had dried but, when he put them on, they felt stiff and rubbed his heels and the tops of his bare toes. To make matters worse, Tessa’s vigorous buffing had removed the polish and, as he had feared, a white tide mark wavered across the insteps. ‘Mum’ll be mad.’

Tessa shook her head. ‘No, she won’t. She won’t even notice. The baby’ll take up all her time and she won’t bother with us any more. Or love us.’

Lewis tugged at his ears, a sure sign that he was anxious. ‘What about Dad? He’ll still love us. Won’t he?’

Tessa had two fathers. One told them adventure stories about a sister and brother, played never-ending games of I-Spy, made bows and arrows from hazel twigs, and showed them how to fold a sheet of paper into a boat that really floated. The other banished their friends from the house, retreated behind the newspaper and refused to listen, flew off the handle at nothing at all and slapped the backs of their legs. Lewis said that their father would still love them but she wasn’t convinced.

His sudden tempers scared her. Once, smarting from what she considered to be an unjust outburst, Tessa had run crying to her mother. ‘It’s hard to explain,’ her mother had said, ‘but Dad gets fed up sometimes. His leg gives him pain. It stops him sleeping and he gets … crabby.’ She’d heard the story many times. When he was fourteen, Dick Swinburne had been playing cricket in the street and had skied the ball on to the roof where it had lodged in the guttering. He’d volunteered to get it back but the ladder he was using slipped and he fell, injuring his hip and breaking his leg. As a result of the accident, he wore a built-up shoe and walked with a jerky limp. Tessa barely noticed it but her friends stared and whispered when they came to the house. Her father’s leg might be the cause of his bad moods but there was no call to take it out on her and Lewis. They hadn’t even been born when the ladder slipped.

Heat smothered the garden and drove the children back into the house. They took out a jigsaw and began sorting the pieces, but jigsaws were for rainy days and they gave up, creeping upstairs to read comics from the box that they kept beneath Tessa’s bed, poring over the beloved characters who were more part of their lives than the next door neighbours.

‘It’s not fair,’ Tessa grumbled, flopping back on her bed. ‘Everyone’s away.’

The Swinburne family usually spent two weeks every summer in a caravan in Devon or Dorset. When school broke up, the children waited for their mother to begin filling two battered suitcases with shorts and sunhats, bathing costumes and pakamacs. They’d been saving sixpences in a draw string purse – a Christmas present to Tessa from Diane, her current best friend – to buy a model sailing boat and they planned to change the surplus into pennies for the slot machines on the pier. The previous year, Lewis had perfected his technique for launching one game’s tarnished ball bearings and he managed to get them to clunk into the metal cups every time. This success returned his stake money and earned him another try. By the end of the holiday, he had amassed a profit of one shilling and tuppence, which he spent on ice creams for the family.

This year the suitcases had remained in the attic and, when Tessa pestered, her mother had given an inadequate but ominous explanation. ‘The baby’s due very soon and I have to be near the hospital. Perhaps we’ll go next year.’

Tessa and Lewis’s knowledge of human reproduction was based on the opaque statement ‘babies grow inside their mother’s tummy’ and, over the past months, their mother’s stomach had swollen alarmingly. Voluminous dresses replaced gaily patterned skirts and pretty blouses, giving free rein to macabre imaginings. What was going on beneath those swathes of gathered fabric? She’d also taken to patting the swelling each time she said the word ‘baby’ which Tessa took to be a kind of ritual, like saluting a solitary magpie or crossing fingers when telling a fib. But once the baby had been born, the urge to know the ins-and-outs of the birth had diminished. ‘Probably something to do with her belly button,’ Tessa ventured but couldn’t square her theory with the inconvenient fact that men possessed these intriguing features, too. In his turn, Lewis wasn’t keen to dwell on any of it, afraid that it might be distressing like the animal carcasses he tried to avoid seeing when they passed the butchers’ stalls in the Central Market.

They messed about for the rest of the afternoon, unsuccessfully pestering their grandmother for biscuits and pop, finally returning to the far end of the garden to hunt for caterpillars on the leaves of the wilting sprout plants.

Dick Swinburne – only his schoolteachers had ever called him Richard – finished work at the General Post Office at five-thirty but for the past week he’d gone straight to the hospital, not getting home until well after Tessa and Lewis had finished tea. Once he’d given his mother-in-law the latest news, she was released from duty and went to catch the bus back to her terraced house on the other side of town.

‘Have you two behaved yourselves for Gran?’

‘Did she say anything?’ Tessa asked.

Ignoring her question he turned to Lewis. ‘Have you?’ he repeated.

‘Yes, Dad,’ Lewis answered, thankful that his stained sandals were hidden in the shadows under his bed.

‘Good, because I’ve got some news.’ He settled in his shabby

leather chair, patting the wide arms where the children perched when there were stories to be told or news to share. ‘Jump up.’

Tessa could tell from his tone that he was in a good mood as she and her brother took their places, draping their skinny arms around the back of the chair behind his head. ‘What?’

‘Can’t you guess? I’ll give you a clue.’ He shut his eyes and leaned his head back and she marvelled at the tufts of gingery hair which burst from his nose and ears and the darker bristles, erupting from his chin. ‘Let’s see. Something rather special is happening tomorrow.’

‘We’re going on holiday?’ Lewis suggested.

Tessa, understanding immediately what her father was hinting at, was delighted with her brother’s innocent remark and prolonged the episode. ‘You’re taking us to the circus?’

‘Come on. Think hard.’

His good humour was dissolving so Tessa gave the answer he was looking for. ‘Mum’s coming home?’

‘Well done, Tess. Mum and Gordon are coming home.’

‘Who’s Gordon?’ demanded Lewis. The only Gordon he’d ever heard of was a blue train in the books he borrowed from the library.

‘Gordon is your new brother. We’ve named him Gordon John after your granddad who died in France. I think you’re going to like him.’

The children hadn’t been allowed to visit their mother. Lewis could only assume that this was because the place was in some way terrifying. If he went by his grandmother’s description – ‘He’s a bonny little chap. He’s got your dad’s nose.’ – all he could picture was a kind of blancmange with tufty nostrils.

Worse than that, he and Tessa had not been consulted about the name. Choosing a good name for the succession of pets that had swum, slithered and hopped in and out of their lives, had always been a serious process, not least because of the wheedling involved to get their parents to agree to the budgie, goldfish, white mice or whatever in the first place. Current pets were Pip, a spiteful ginger cat who lacerated anyone foolish enough to get within arm’s length and Speedy the tortoise, who did nothing much. The family had, for three weeks or so, owned a bright-eyed Cairn terrier called Pete who had made a permanent getaway by slipping his lead when supposedly moored to the lamp post outside the library. Lewis thought that ‘Pete’ would make a jaunty name for a new brother. Easy to spell, too. His father’s disclosure that the baby’s name had already been decided was further confirmation that family rules were being re-written as Tessa had warned.

Bells

Bells A Different River

A Different River Sweets From Morocco

Sweets From Morocco Not Funny Not Clever

Not Funny Not Clever Left and Leaving

Left and Leaving Everything in the Garden

Everything in the Garden